By now you have probably heard about the extremely embarrassing LinkedIn password breach. If you have a LinkedIn account (or possibly, if you have ever had one), there is a good chance that your password, in a weakly encrypted format, is in the hands of a hacker in Russia. He published as proof a massive, 6-million password file that is now widely available on the internet. There’s even a service that guides you through the process of searching for your password in the file (link courtesy John Moltz).

I did what you did, or should have done: raced to LinkedIn and changed the password. But that doesn’t protect me from the real danger. LinkedIn isn’t anywhere near the most important site in the huge list of services I use or have used. What if I committed the foolish move of using the same password on LinkedIn as I did on another, more important site? Now a hacker with possession of my username and password for LinkedIn can make some very good guesses about my username and password on other sites.

Fortunately, I don’t tend to use the same password twice. But an event like this leaves me very curious to confirm that. I store all my internet passwords in Apple’s Keychain, which does a good job of keeping them from prying eyes. A little too good of a job, as it turns out. There’s no straight-forward way to ask Keychain Access on the Mac to find all the services that you used a specific password with. So if my LinkedIn password was “bugagoo,” to find out which other services I might have used that password for, I have to open each password item in the keychain and authorize Keychain Access to show me the password. 2,000 times, in my case.

This is a situation that screams for scripting. Surely I could come up with something, using the security command-line tool or AppleScript, to go trawling through my keychain looking for suspect items? I happen to have written an AppleScript helper called Usable Keychain Scripting, that makes a script like the following very easy to write:

tell app "Usable Keychain Scripting"

get internet passwords of keychain 1 ¬

where password is "bugaboo"

end tell

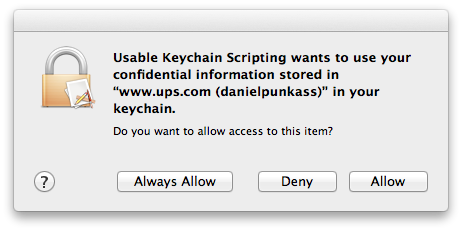

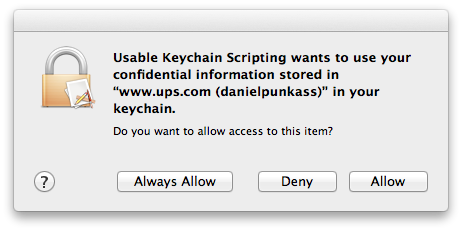

Unfortunately what you get when you run a script like this is an alert like this for every keychain item being searched. Like said, for me it’s more than 2,000 items:

The problem here is that permission to access keychain items is managed on a granular level. It’s possible to tell the security system to allow a particular app to always access a particular item, but you can’t tell it to always allow it to access the entire keychain. There are obvious security reasons for this, but I do think there should be way to enable this for folks like myself who really want to take control over my secure data and examine it programatically.

Fortunately, I do not give up easily. I could have clicked that Allow button 2,000 times, but then I wouldn’t have had the time to write this blog post. Instead, I delved into another avenue of scripting that takes advantage of Mac OS X’s accessibility infrastructure. Using GUI Scripting commands, the clicking of specific buttons can be automated. In this case, I came up with a script that runs in a loop, waiting for there to be a security window with a button called “Allow” in it, and indiscriminately clicking it. Obviously, this is very dangerous! I’m going to run this script only during a precise window of time where I know that the only security dialogs coming up should be ones that are provoked by my Usable Keychain Scripting script.

This trick worked. After 20 minutes or so of chugging through my keychain and automatically approving the accesses, the result came back. To my relief: the password was only used for LinkedIn.

You can use this trick, too. Just be careful. As I said above, the idea of an automated script that blindly approves security warnings is not for the faint of heart. It should go without saying that if you screw anything up in your keychain, it is unequivocally not my fault. Do not use these tools if you don’t understand how they work.

- Usable Keychain Scripting is my scripting extension, that expands AppleScript’s ability to efficiently query the keychain for information.

- PasswordSearcher is an AppleScript that asks the keychain for all the internet password items that match the given password, and displays the account names so you know which ones to look for.

- DangerousAllowClicker is the bad boy that just runs in circles until you cancel it, approving security clearances.

Click here to download the tools archive.

To use these:

- Launch Usable Keychain Scripting, so it will be available to the scripts. You won’t see anything, it is a background-only app.

- Open Password Searcher, change the password string to match the one you want to search, and run it. You should immediately see one of those security approval dialogs appear. Don’t bother clicking it.

- Now open up DangerousAllowClicker and run it. You should see the security panel disappear, and successive panels disappear in turn.

Go get a coffee or something because this could take a while, and your computer is less fun to use with security clearances popping up constantly. When you get back, you should see a result. Hopefully your news will be as good as mine, and only LinkedIn will appear in the list. If for some reason you get tired of waiting, or nervous about the technique, you will need to kill the Usable Keychain Scripting application to interrupt its attempt to fulfill the scripting request:

% killall Usable\ Keychain\ Scripting

As I said, this technique is only suitable for the very technically adept, but I am glad to share it because I think some of you will find it useful for other purposes as well. You could theoretically use this trick to automate dumping your password information so as to import it into another management tool such as 1Password. A tool that, as it happens, does allow you to search all your items for a specific password.

I can’t stress enough how void of a warranty, guarantee, support, or any liability these tools are. You shouldn’t use them, but I hope that reading about them has been interesting.

Update: As luck would have it, mere moments after publishing this, I got word from the 1Password folks about another write-up that achieves something different (exporting for 1Password), but makes use of the very same approach of automating the clicking of that allow button.