If you’ve been following the debate surrounding Apple’s Application Sandbox, you know that many developers are concerned about the implications for existing apps of adopting the sandbox.

Apple has been threatening for almost a year that apps for sale in the Mac App Store will need to embrace the Application Sandbox, or else further updates to the apps will not be accepted. The deadline for adopting the sandbox has slipped several times, but it currently rests at June 1, 2012. That’s only a few weeks away, and comes just ahead of Apple’s annual developer conference.

I’ve written a few rants about the Application Sandbox, culminating in my February 2012 piece imploring Apple to “Fix the Sandbox.” Slowly but surely, they are improving the technology that drives the sandboxing features of Mac OS X, but by June 1, it appears that many classes of application will still be “unsandboxable” under the current permissions model supplied by Apple.

The shortage of permissions, or “entitlements” in sandbox lingo, has always been at the root of my concerns. Especially because of the political move requiring existing Mac App Store apps to adopt the sandbox, it is easy to imagine a features bloodbath come June, or whenever the requirement goes into place. When Apple announced the postponement to June 1, they also took care to make assurances that bug-fix updates would still be allowed for non-sandboxed apps, which is a nice break, but will still leave many apps to die on the vine in lieu of suitable sandboxing entitlements for the features various apps provide.

Apple publicly documents the list of entitlements available to Mac software developers. One of my major concerns has always been that because the list of entitlements doesn’t cover all the nuanced, legitimate tasks that an app might want to perform on a user’s behalf, that Application Sandbox ran the risk of permanently forbidding certain types of application behavior from being conducted in the sandbox.

The high-level list of Application Sandbox permissions is intentionally coarser-grained than the lower-level “sandbox facility” which ultimately imposes the restrictions. Some developers criticize Apple for failing to embrace the sanbdbox with their own apps, while expecting developers to embrace it for the Mac App Store. On Mac OS X 10.7.4, the two notably sandboxed apps from Apple remain Preview and TextEdit, two apps that would be relatively simple to sandbox compared to a large number of complex, 3rd party products.

But Apple has applied a good deal of sandboxing to their code. For example, take a look at /usr/share/sandbox/ and /System/Library/Sandbox/Profiles/ for examples a variety of “.sb” files that specify the sandbox restrictions of a variety of system services and tools. These files are expressed in SBPL, or the Sandbox Policy Language, which is a scheme-based language used to express the fine-grained permission the sandbox facility is capable of controlling. See my “Sandbox Corners” for a bit more about the lower-level sandbox facility and SBPL files.

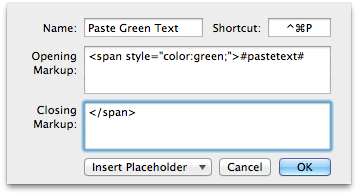

Today I decided to take a closer look at one SBPL file of particular interest: /System/Library/Sandbox/Profiles/application.sb. This is the SBPL file that, so far as I can tell, translates the high-level “entitlements” of the Application Sandbox into corresponding lower-level policy expressions for the sandbox facility. For example:

(if (entitlement "com.apple.security.network.client")

(allow network-outbound (remote ip)))

You can get a taste for how the high level “I’m a network client” translates specifically to “allow out bound ip traffic” at the sandbox facility level. Other high-level rules express much more complex logic. For example, the “I want to use the printer” entitlement translates to a variety of low-level permissions to communicate with printer-system daemons, and read from printer configuration files on the system.

But by far the most interesting entitlement of all is one that I found at the bottom of application.sb. It’s not documented on Apple’s site, and from what I can tell this blog post will become the first Google match on the term. The entitlement is “com.apple.security.temporary-exception.sbpl”, and the comment above it reads simply: “Big Red Button”.

;; Big Red Button

(sandbox-array-entitlement

"com.apple.security.temporary-exception.sbpl"

(lambda (string)

(let* ((port (open-input-string string))

(sbpl (read port)))

(eval sbpl))))

This temporary entitlement enables a high-level Application Sandbox-restricted application to supply, along with whatever other high-level entitlements it requests, an entitlement that brings with it as a parameter a literal SBPL program, that will be evaluated and thus applied by the lower-level sandboxing facility.

In short: the Big Red Button gives Apple an out.

Whatever mistakes they make in the devising of high-level entitlements can be theoretically undone after-the-fact by supplying developers with special Big Red Button entitlements that pass along specific permissions to the lower-level sandbox, liberating the application to do whatever important task it needs to do.

Of course, the fact that this facility exists does not say anything about whether Apple will indulge its use. And just because you, as a developer, could use this entitlement key to empower your sandboxed app to do practically anything, it doesn’t mean that Apple’s App Store reviewers would look kindly upon it. In fact, I’m almost positive that at this point, any developer who submits a sandboxed app with this entitlement will have to have already conversed extensively with Apple about the need for such a transgression.

But the entitlement is there, and that makes me breathe a little easier. The Application Sandbox is, so far as I can tell, technically capable of granting whatever permission any app could reasonably need. The only obstacle, and it’s a big one at that, is the political challenge of App Store approval.

Update: John Brayton made an interesting point in the comments, that regardless of MAS policy, the Big Red Button might be useful to non-MAS developers who wish to adopt the Application Sandbox , but can’t manage to squeeze all their functionality into the confines of its entitlements. I originally thought this made good sense, but then realized how risky a move this would be in practice. Because the entitlement in question here has not been documented by Apple, and is furthermore only listed in an implementation file for the system itself, the behavior of this entitlement can’t be relied upon.

Indeed, above I suggested that the entitlement would grant developers the power to enable virtually any capability in their sandboxed apps, but we have no idea how Apple has actually implemented support for the entitlement inside Apple. They could very well have a special case inside the SBPL language evaluator itself that looks for and rejects scripts that it doesn’t recognize as its own.

The application.sb file even has a strong disclaimer to this effect:

WARNING: The sandbox rules in this file currently constitute

Apple System Private Interface and are subject to change at any time and

without notice. The contents of this file are also auto-generated and

not user editable; it may be overwritten at any time.

In other words: you can’t count on the details of this file remaining stable from release to release. It would be foolish to base the behavior of any shipping app on entitlements listed there, but not documented by Apple. I think the Big Red Button is a very interesting find, and I’m very curious about it. But that’s how it should be considered: as a curiosity.