Macintendo Family Values

December 28th, 2006Disclaimer: This article is not news. It is humor as a backdrop for high-level analysis. Please do not cite it as a rumor, or even as speculation.

The “announcement” is not based on any factual information that has been made available to me. Although I enjoyed the fantasy of a Nintendo/Apple partnership as a backdrop against which to write about some of their apparently shared values, I have no expectation that such a partnership is actually in the works.

I thought the humor was clearer than it turns out to have been. A substantial number of people seems to have misread the tone of the article, and I’m sure that some of you feel deceived. I’m deeply sorry for that – in no way did I intend to mislead you.

If you were misled by this article, perhaps one good thing to take away would be an insistence on “checking sources.” Without absolving myself, I will point out that had you done so in this article, you’d find that the “news” came my way “when the popular Nintendo character Yoshi bounced into the office and delivered the news.”

Thanks for reading, and I’ll try to make my satire a bit clearer in the future.

Daniel Jalkut

PS: Steve Jobs lives in a secret underwater castle with mermaid servants.

Nintendo and Apple Announce Strategic Partnership

Nintendo Co. Ltd. and Apple Computer Inc. today announced a multi-year, strategic partnership had commenced earlier this year and will culminate in the January 9, 2007 launch of the partnership’s first product: Podfondo. The partnership aims to leverage the technologies, trademarks, and patented processes of each company to produce products that satisfy a growing consumer demand for elegant, usable products in the consumer electronics market.

Development of Podfondo, a combination mobile telephone, music player, and portable game system, was completed only 9 months after an exploratory meeting between Apple CEO Steve Jobs and Nintendo’s Satoru Iwata took place on April 1, 2006. Public rumors of the partnership have been minimal, thanks to strict secrecy policies already in place at both companies. Some analysts speculate that the two companies were inspired by Todd Ogasawara, who earlier this year suggested that Apple should buy Nintendo. While most observer agree that an outright acquisition will never happen, the idea of a strategic partnership has been explored in some detail. Now at last we can put the speculation to rest and take a look at what the companies have actually been doing.

The Macintendo alliance operates semi-independently, staffed by a core team of engineers, designers, and marketers from each company. While Macintendo personnel have full access to the technologies and workforce of the respective companies, it is expected that it will continue to operate as an independent and self-sustaining enterprise. In fact, the Macintendo enterprise is currently expanding its ranks, and is pulling a massive number of new recruits in from mainstream Apple and Nintendo employee pools. In order to ensure that the quality of Macintendo products remains high, the nascent partnership has compiled a list of “family values,” which serves to condense the shared priorities of Nintendo and Apple into a brief document – one that may be frequently referenced by members of the Macintendo team. By remaining focused on these key ideals, it is hoped the team will continue satisfying consumer demand for innovative entertainment products, even as it grows rapidly.

We at Red Sweater Software were lucky enough to be among the first to learn of this unbelievable development, when the popular Nintendo character Yoshi bounced into the office and delivered the news, along with a complete copy of the previously confidential family values document. We are pleased to be able to reproduce this document publicly, in its entirety. As an indie developer, I’m not sure I agree completely with the “Product Then Platform” family value, but I can sort of see the logic.

Welcome, Nintendo and Apple employees! This document was created to welcome you to the Macintendo family and to codify some of the values that make each of our companies as successful as they are. Working together as a team, we’ll be able to bring customers products so fantastic that even our retrospective companies could never dream of achieving them alone.

Please take a moment to review this document now. You may also refer back to it from time to time as you work through the design, engineering, and marketing issues that you encounter during the Macintendo product development cycle. Thank you for joining us in this exciting enterprise!

Underwhelming Features, Overwhelming Functionality

Manifesto: Macintendo is opposed to features for their own sake. Our products are designed to perform only the tasks necessary to fulfill the primary product goals. We are prepared to accept criticism for the relative lack of features our products possess, because we know that focusing on the functionality will ultimately astound our customers, generating insurmountable brand loyalty.

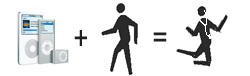

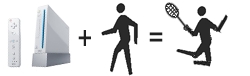

At Macintendo, be believe in a simple formula. Our product + our customer = primary product goal.

Apple Keystone: iPod. Apple entered an existing market, identifying “managing owned music” and “listening to owned music” as primary product goals. In an environment where existing market forces were furiously adding features such as voice recording and FM radio, Apple recognized the consumer’s desire to “manage and listen to owned music.” Apple underwhelmed the press with the iPod’s relative lack of features, but overwhelmed consumers through its simplified attention to their needs.

Nintendo Keystone: Wii. While Microsoft and Sony battled furiously to outdo one another’s graphics and video playback abilities, Nintendo clung to its famous reputation as funmaker. The Wii’s primary product goal is to “let the user have a fun time.” Costly video capabilities and high-definition DVD technologies have made the competing products money-losers, even at twice the retail price of the Wii. Nintendo focused on evolving the user interaction to include a kinesthetic controller. Underwhelming video and graphics, overwhelming fun.

Podfondo Example: Podfondo was a challenging product, being relatively feature-heavy by definition of its combined target audience. But by factoring common behaviors and applying a common user interface to each of the three primary functions, we achieved our primary product goal: “to provide users with a unified device for managing music, staying in touch, and having fun.” Consumers who participated in our confidential trial testing are already excited by the simplicity a single cohesive device has brought to their lives.

Iconic Branding

Manifesto: Macintendo appreciates the value of brand recognition, and strives to leverage the branding of its respective companies. To whatever extent existing trademarks or interactive metaphors may be leveraged to benefit the consumer, they shall be.

Apple Keystone: The Apple company logo is itself among the most recognized brand images in the world, having reached a status where even the silhouette shape instantly evokes an impression of quality and elegance.

Nintendo Keystone: Nintendo’s brand is helped immensely be a cast of recurring characters who never fail to entertain consumers. Nintendo’s beloved plumbers, mushrooms, dragons and elves bring with them an immediate expectation of fun.

Podfondo Example: The Podfondo logo seeks to capture audience recognition of both the Nintendo and Apple logos by incorporating them into an elegant design that embodies quality and innovation.

Innovate For Simplicity

Manifesto: Macintendo believes that product innovation must serve one or both of these purposes:

- To improve the user’s chances of achieving a primary product goal.

- To reduce the complexity of a user’s interaction with the product.

Macintendo expects every team member will evaluate their own innovations in terms of these criteria. Innovations that add complexity to a product must be judged unanimously to greatly improve the user’s ability to achieve a primary goal. Innovations that do not satisfy these criteria are not welcome in Macintendo product designs.

Apple Keystone: iMac. Apple’s introduction of the iMac personal computer epitomized innovation for simplicity. In particular, one of the product’s primary goals, “getting connected to the internet” was famously described in television commercials as having “no step 3.” By innovating for simplicity, Apple encouraged adoption of a complex microcomputer by customers who might otherwise be intimidated by such a product.

Nintendo Keystone: DS Lite. With the DS Lite portable game system, Nintendo innovated for simplicity by looking beyond the conventional keypad input method commonly used in computer-human interfaces. The DS Lite comes standard with a microphone suitable for voice input, and with a stylus and touch pad suitable for handwriting. By adapting the computer to the user, instead of asking the user to adapt to the computer, Nintendo greatly expanded the accessibility of the product while adopting communication metaphors familiar to most users.

Podfondo Example: Podfondo innovates for simplicity by factoring the common interface metaphors of the iPod and Nintendo DS Lite into a single device, while drawing on the strengths of each to provide extremely intuitive voice, video, and live text messaging functionality. The iPod’s familiar hierarchical menu interface serves as the “front door” to a variety of context-specific functions and interfaces. A DS-inspired touch screen represents the familiar scroll-wheel of the iPod, which may be operated by thumb or with the supplied stylus in the usual way. In addition to conventional hierarchical menu, Podfondo takes advantage of advanced voice recognition and stylus gestures, borrowed from the DS Lite. Podfondo’s advanced motion analysis can quickly detect whether a particular movement is intended as circular scrolling motion, or as a more advanced gesture. A number of top-level complex gestures are pre-defined as shortcuts to the various functions of the Podfondo, and custom gestures may be defined by users to, for instance, call a particular phone number.

Although most Macintendo innovation comes from within the extensive Apple and Nintendo talent pool, on occasion we find it expedient to incorporate innovations from outside the two companies. In this example, technology was licensed from the industry-leading gesturing application, FlyGesture, to make the Podfondo as user-friendly and intuitive as possible.

By providing a consistent, familiar interface, Podfondo is simple for anybody to use. With the addition of voice and gestural shortcuts, it remains simple while still providing a great deal of customization.

Product Then Platform

Manifesto: Macintendo recognizes the value of products with extensible platforms, allowing other companies to expand the product’s offering and improving overall appeal to customers. To this end we make platform development a major, but secondary priority in the product development cycle. We insist on ensuring a product’s viability in its own right, if necessary at the expense of and detriment to third-party developers. Product then platform is our mantra when it comes to devoting resources to APIs, tools, and support for third-party development.

Apple Keystone: OS X Bundled Applications. Apple’s standard bundle of included applications includes everything the average user needs to fulfill the primary product goals for a personal computer. Mail, web browsing, simple text editing, an address book, and calendar are all included for free with any Macintosh computer. Additionally, most computers include a standard package of “iLife” applications, which allow simple video editing, music recording, etc. On the platform end of the spectrum, Apple makes a reasonable effort to encourage third-party development by providing free development tools, documentation, and code examples.

Nintendo Keystone: In-House Development. Nintendo guarantees a complete product for their customers by taking responsibility for the most iconic products for the platform. In this way, their approach is similar to Apple’s, but more comparable to the for-sale products that Apple offers such as iWork, Final Cut, Filemaker, etc. By controlling the hardware, operating system, and a great deal of the software, Nintendo ensures a passable experience for any customer who buys their product. In the development tools department, Nintendo is less giving than Apple but still supportive of third-party development through a kit that costs upwards of $2000. By limiting access to the development kit, Nintendo ensures that for the most part only serious development companies are allowed access to the platform, thereby setting a high standard for products that appear on the market.

Podfondo Example: Podfondo was lucky in that a majority of the hard development work had been done by the respective companies, for the products that preceded it. Development of the Podfondo was largely a feature-management and integration job, and it gained the “product-making” features of its ancestors. Thanks to this, the team was allowed to give an unprecedented amount of thought to the question of third-party development.

In the end the team decided, with the permission of top executives at Apple and Nintendo, to take a much more open approach to supporting platform development than with previous products. Starting with Podfondo, the iPod operating system has been standardized with a completely extensible third-party API. The software has been developed in such a way that existing iPods (4th generation or higher) may be upgraded to the modern, extensible version of the iPod/Podfondo firmware. Nintendo management has also agreed that for all products developed under the Macintendo joint venture, game development kits will be made freely available to developers registered with a free Apple Developer Connection membership.

Macintendo believes that the Podfondo product is so strong, than an open, highly extensible platform for third-party development can only increase customer acceptance and the overall quality of the brand.

Make It Real. Then Make It Really Good.

We’re glad to have you on board at Macintendo, and we look forward to building the future of consumer electronics with you. Making it real, and making it really good, are the most important family values of all. In 2007 we’ll invent the unexpected, and then we’ll perfect it. Thanks to you. It’s going to be a heck of a year!