I’ve been working on iTunes integration for FlexTime. My model for this feature is roughly approximated by GarageBand’s “Send To iTunes” feature, which packages up the current song into an M4A format, sends it off to iTunes, starts playing it, and makes sure the playlist into which it was added becomes visible in the iTunes browser window.

It’s pretty obvious to me that the way to get this done (at least after converting the audio to M4A) is via AppleScript. iTunes is respectably scriptable, but getting specific things done can be infuriatingly cryptic. The first several steps of the workflow are easy, being either standard AppleScript commands, or commands that are easily found in iTunes’s AppleScript dictionary:

- Activate iTunes. Just use the “activate” command.

- Make a new playlist. Not entirely obvious, but you get used to this in AppleScript. Just “make new user playlist with properties” works well.

- Add the new track. iTunes offers “add” to “add one or more file to a playlist.” Perfect!

- Set details on track. Simple attributes exposed as writable on the “track” object in iTunes’s dictionary. “set artist of,” “set album of,” etc.

- Play the track. Easy! “play” is exposed to “play the current track or the specified track or file.”

- Select the track’s playlist. Umm. Help? There’s a bunch of false positives here: “selection,” “current playlist,” etc. But they’re all marked as read-only attributes, so we’re out of luck.

The user experience if you don’t show the track’s playlist is greatly reduced, because the track just starts playing, but iTunes is still pointed at whatever the user was looking at before. To find it, they’ve got to intuit the name you gave it, and search for it. Ugh! (Note, it could be argued that just taking control away from whatever the iTunes focus was is rude, but I think it’s fair to say that it’s non-destructive and that the user will just “get over it” or else stop using this feature).

But GarageBand does it! How does GarageBand do it? The smart thing to do now is to throw up your arms and race off to some site where they’ve already figured all of this junk out. Doug’s AppleScripts is a treasure chest of scripts specifically for iTunes, and of course it includes several that show exactly how the selected playlist can be changed. The naming is tricky, but it’s simple.

Of course, I’m a dumb technophile, so my first instinct is not to run off to some site where the solutions are obvious. Instead, I decide to play detective and figure out what the hell is going on. In situations like this, I can almost guarantee you that AppleScript (or at worst, a raw AppleEvent) is being used to achieve the desired inter-application control. There is such a rich legacy of AppleEvent based interaction between applications, that even if Apple were to add a super-secret “for GarageBand only” control mechanism, it would likely be in the form of an AppleEvent.

So we break out the AppleEvent spycam. You can observe all the incoming or outgoing events for an application by setting the AEDebugReceives and AEDebugSends environment variables, respectively. From Terminal:

% cd /Application/iTunes.app/Contents/MacOS

% AEDebugSends=1 AEDebugReceives=1 ./iTunes

Now when you “Send To iTunes” from GarageBand you’ll see an avalanche of event data racing across the terminal window. This is pretty overwhelming. In fact we could have just looked at “Receives” to cut down on the chatter, but even that would give us a lot material to sift through. Take a deep breath and start scanning for demarcation points.

AE2000 (6804): Received an event:

------oo start of event oo------

{ 1 } 'aevt': core/setd (i386){

The first three lines of an incoming event’s content are pretty easy to parse, once you know what to look for. The first line tells you it’s a “received” event, so something is asking the target application (iTunes) to do something. The third line is the highest level summary of what that something is, containing information about the event’s class and ID. This one’s an AppleEvent (aevt). It’s class is kAECoreSuite (core) and its ID is “kAESetData” (setd). In plain English? This event corresponds to an AppleScript “set” command.

In AppleScript, events usually carry a command to do something as well as a bunch of cargo representing the target of the command as well as any other parameters that are pertinent. Once you’ve deciphered what a particular event’s high level meaning is (the command to be performed), the next most interesting thing to scan for is the collection of parameters that are attached to it. The log is pretty daunting, but it helps to focus on things hierarchically and just make sense of each parameter “object” one at a time. I’ve color coded the event data to make the hierarchical structure pop out a bit more:

event data:

{ 1 } 'aevt': - 2 items {

key 'data' -

{ 1 } 'obj ': - 4 items {

key 'form' -

{ 1 } 'enum': 4 bytes {

'name'

}

key 'want' -

{ 1 } 'type': 4 bytes {

'cPly'

}

key 'seld' -

{ 1 } 'utxt': 48 bytes {

"........................"

}

key 'from' -

{ -1 } 'null': null descriptor

}

key '----' -

{ 1 } 'obj ': - 4 items {

key 'form' -

{ 1 } 'enum': 4 bytes {

'prop'

}

key 'want' -

{ 1 } 'type': 4 bytes {

'prop'

}

key 'seld' -

{ 1 } 'type': 4 bytes {

'pPly'

}

key 'from' -

{ 1 } 'obj ': - 4 items {

key 'form' -

{ 1 } 'enum': 4 bytes {

'indx'

}

key 'want' -

{ 1 } 'type': 4 bytes {

'cwin'

}

key 'seld' -

{ 1 } 'long': 4 bytes {

1 (0x1)

}

key 'from' -

{ -1 } 'null': null descriptor

}

}

}

You can see that this event has two fundamental parameters (in blue) attached to it, each identified by a unique 4-character code. Parameters with a type of ‘----’ are sort of ubiquitous in AppleScript – they are referred to as “the direct parameter,” which is the “thing” on which any given command has its effect. In this case, it’s what we’re setting the value of. The other object here is identified as ‘data’, which should be pretty easy to figure out. That’s the cargo that represents the actual new value. For example in the AppleScript: ‘set title of window 1 to “bob”‘, the direct parameter is “title of window 1” and the data is “bob”.

You don’t have to be a genius to know where we’re going next. What the heck is the direct parameter, and what the heck is the data? We have to dig a level deeper. In color-coded terms, we’re now curious to decipher the meaning of the green and purple stuff.

These portions of the AppleEvent are composed of magically coded data that instructs the “Object Support Library” portion of the Apple Event Manager to resolve them in well-defined ways. The most common codes are defined in AEObjects.h. While you’re investigating a situation like this, it can be handy to keep that header file open. Codes not found there are probably defined by scripting definitions, which expand upon the basic built-in functionality by providing support for new properties, commands, etc.

Let’s look at the direct parameter first. It’s an object composed of four directives, identified by the codes ‘form’, ‘seld’, ‘want’, and ‘from’. These codes are all defined in AEObjects.h, and explained more thoroughly in the constants section of the Apple Event Manager Reference. All the same, a bit of plain-speakin’ would probably be appreciated right now. But before I do, let me add the disclaimer that I don’t really get all this. I only get it well enough to meet the task at hand. So with that said, and the real possibility of my making subtle technical mistakes, let’s get moving.

Basically, the ‘form’ is identifying what kind of object we’re talking about here. In this case, it’s a property (‘prop’). OK, this a property reference. Kind of like “name of window 1” is a reference to the “name” property of a given window.

Next up we’ve got ‘want’, which appropriately enough identifies the type of object we’re trying to identify. I think this is generally useful for coercions, situations where you say “count of windows as string.” You can tell the Apple Event Manager that what you’re looking for is a property, but you’d like it as a string instead. In this case, we’re happy to have the object remain a property reference, because we’re just trying to point at it for AppleScript’s sake.

The first really intriguing key is ‘seld’, which means “the unique interesting data,” i.e. the meat. The content is a type ‘pPly’. Hmm, that’s nothing standard. We’ll have to file that away for later.

Finally, we have the ‘from’ key, which is also mnemonically appropriate, in that it identifies the container from which this item (property in this case) should be fetched. If you look at the contents of the ‘from’ data, you’ll see that it’s basically a recursive exercise in applying the same code interpretation we’re doing here. So what do we have so far? If we try to mimic what we see in pseudo-AppleScript it looks something like this:

set 'pPly' of '????' to '????'

Still a lot of variables, but we know how to figure out the details. Just keep looking at codes and making sense of them. So that I don’t spend all day typing, maybe I better skip ahead and say that the purple stuff is an indexed object specifier that refers to “window 1” of the application (a null ‘from’ means the top-level container). For the ‘data’ parameter’s contents, the ‘????’, we run into many of the same referential tags. This time it’s a named object with a type code of the mysterious ‘cPly’ variety. You can probably make sense of that now by studying the details carefully. With our newly decoded information we’re left with the following:

tell application "iTunes"

set [property 'pPly'] of window 1 to [class 'cPly'] "......"

end tell

Hey! This is starting to look like AppleScript. I’m going to assume the ‘utxt’ with all the “……” is just the AppleEvent log failing to read the actual text out. The real mysteries now boil down to this property ‘pPly’ and this class ‘cPly’. What’s a hacker to do? If we’re lucky, and it turns out that we are, we’ll find these constants defined in the iTunes scripting dictionary. There are two ways to go about this. We could always examine the target application’s resources. In this case iTunes stores the scripting information inside its iTunes.rsrc file. Lots of newer applications use more text-friendly browsing formats such as script suites or sdef files. But we can use a little hack involving the Script Editor to take advantage of its parsing the scripting information and converting it to an sdef file.

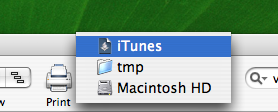

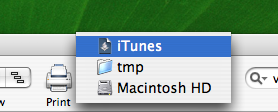

The best thing about this hack is you’ve probably already got the target application’s dictionary open in Script Editor. The beauty is, the dictionary window in Script Editor is an opened document to an sdef file in a temporary directory. Just cmd-click the title bar to reveal its location, and select it:

Now you can open the sdef with a standard text editor and search for whatever raw codes you like. When I searched iTunes for our mystery codes, I discovered the following interesting lines:

<property name="view" code="pPly" type="playlist"

description="the playlist currently displayed in the window"/>

<class name="playlist" code="cPly"

description="a list of songs/streams"

inherits="item" plural="playlists">

Cool! Those are our mystery codes. And their definitions above lead us exactly to the answer, giving clear AppleScript names and meaning to the codes we’re examining. We could have found this by browsing the dictionary with a fine-toothed comb, but when I was looking for the desired attribute, I was fooled by all the false positives. I never considered that the property might be named “view” and that it might be an attribute of the window instead of the application itself. Heck, the code is more intuitive for “playlist” than the actual property name. View?! Anyway, the resulting victory script is as follows:

tell application "iTunes"

set view of window 1 to playlist "My Favorite Songs"

end tell

Next time you’re sure there’s a way to script something, but can’t for the life of you figure it out, go find a really useful site like Doug’s AppleScripts. Or if you’re a masochist maybe you’ll find a way to put some of these techniques to work, instead.