Fast Unit Testing Iterations

March 31st, 2009It’s not as though unit testing is completely new to me, but even years after I wrote my first tests, I still consider myself a naive amateur in many regards. I’ve been ramping up my use of tests lately thanks in large part to a technique I read about in Michael Feathers’s book Working Effectively With Legacy Code.

Essentially, the idea is that before you do any major refactoring in your existing code base, you should attempt to locate a “bottleneck” to how that code is reached, and test the interface at that bottleneck. So, if all the code paths to Class A and Class B are through Class C, I can effectively just cover Class C with unit tests and be relatively certain that the functionality of Classes A and B are covered to the extent that I care about them.

Refactoring then becomes a lot less stressful, because you’re more likely to catch stupid mistakes and changes in functionality you might cause in the process. I realize that no set of tests is a guarantee against introducing new bugs, but in the process of covering classes with test coverage, you also end up learning quite a bit about what the classes actually do. This is no small victory when working with code that you either didn’t write, or that you haven’t reviewed in a number of years.

As I’ve become more and more dedicated to testing in my Mac and iPhone projects, the size of my test suites has grown. I’m subscribing to guidelines for good test writing: that they should be fast and as isolated as possible. But they still take a non-trivial amount of time to run. It’s gotten to the point where the tests for my “web publishing frameworks” take at least a minute to run on my MacBook. This is pretty fast in the big scheme of things, but a long time to wait when I’m engaged in a rapid edit, build, and test iteration.

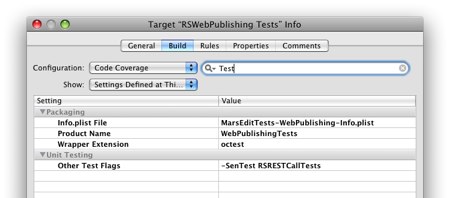

I figured there must be some way to limit the test cases that get run to just the specific one I’m working on at the moment. And it turns out there is. Thanks to the “Other Test Flags” build setting in Xcode, I can temporarily change the behavior so that it runs only a subset of all the tests contained in my test bundle. For example, right now I’m working on tests that cover the functionality of my RSRESTCall class:

The -SenTest option is passed on to the test rig, in my case the default “otest” command that comes with Xcode. This lets the test rig know that instead of the default behavior of finding and running every test in the bundle, it should just run the tests in the “RSRestCallTests” SenTestCase subclass.

Something I didn’t mention yet but which is also aiding me greatly in the measuring my test coverage is the “gcov” library that also comes bundled with Apple’s developer tools. I’m using this to create a “Code Coverage” build of my code, that makes it possible to see exactly which lines of code did or did not get run during a particular set of tests. This, in conjunction with a cool application from Google’s Mac developers, makes it pretty easy for me to seek out uncovered areas of code, think about how to cover them with tests, and iterate.