I spent a large part of today “under the hood” working on this blog’s WordPress-based engine. My head hurts from all the PHP, but I am pretty happy with the results. What was I doing? Optimizations for CPU and bandwidth efficiency.

I have been pumping up DreamHost since I moved over to them a couple weeks ago. They’re still awesome, but the honeymoon did end a little bit when I got an email from them notifying me that I was exceeding my daily CPU usage allotment. Hmm? I had never even considered this before. I guess I just took for granted that servers were good and fast and they made it all work. I didn’t consider that with a virtually unlimited bandwidth quota, I would have to watch my step with how hard the server was working to fill that pipe.

I’ve been oblivious to web performance considerations, for the most part. This wake-up call from DreamHost inspired me to finally take the problems by the horns. When your site only gets a half-dozen hits per day, who cares how well it performs?. But as my traffic continues to increase, I’m starting to look at things more and more like a webmaster.

Some time ago I was chatting with John Gruber about the merits of WordPress vs. Moveable Type. He pointed out that WordPress, with its dynamic content generation, was a lot less likely to stand up to a major traffic burst than Moveable Type with its static generation. Frankly, it was the first time I’d even considered the issue – and it scared me so much it almost made me want to jump ship from WordPress. How could it be so inefficient? Basically every WordPress blog comes standard with a complete and utter inability to stand up to being slashdotted? Given the amount of traffic Daring Fireball must receive, it’s no surprise that John’s thought about this problem a lot.

But what was I going to do? Switch from WordPress? Please, no! Thankfully, the amazing WP-Cache WordPress plugin basically fixes all that. By saving a static copy of every dynamically generated request response, it achieves the best of both worlds by allowing content to be dynamically generated, but letting it stick around for a while on disk for future servings. Today I installed and activated the plugin. When the cache is on, every request that is answered gets appended with an HTML comment describing whether the request was cached or dynamically created, and how long the original dynamic creation took. I was curious to know how much time I was saving on the cached copies, so I hacked the plugin to also print a timestamp when the cached version is served. The results are pretty impressive. For example, on one entry I just looked at from my browser:

<!-- Dynamic Page Served (once) in 0.453 seconds -->

<!-- Cached page served by WP-Cache in 0.002999 seconds -->

In other words, it went from almost a half-second to almost no time at all. A huge reduction, most of which I assume would be spent as CPU time in the dynamic case. Curious about whether the cache saved you any time just now? Just look at the source for this web page or RSS feed, at the very bottom you’ll see a comment about the dynamic generation time. If it was cached, you’ll see a second comment about that. I haven’t exactly figured out everything that stimulates a cache flush for a particular URL, and it’s possible that the flushing is a little overly-cautious, but at least it’s not serving stale data.

Being so pleased with the caching success, I was in the mood to keep improving things. A reader pointed out a problem a couple months ago, which I’ve been meaning to look into. They had installed the latest beta of NetNewsWire and noticed in that application’s “Bandwidth Statistics” window, my blog was at the top of the heap for bandwidth used. The problem? A combination of my notoriously long posts, a fairly large “item count” for the feed, and a flaw in WordPress 2.0.2 that causes it to not properly return 304 (Not Modified) responses to clients who ask politely whether there have been any changes. So every time NetNewsWire refreshed, it would grab the full text of my last 10 posts!

Today I searched the web and found out that the 304 issue was in fact addressed, and the change is so simple I could type it in to the sources myself. Yee haw! I made the change and rushed over to NetNewsWire to try it out for myself. Alas, it still wasn’t working. The problem now? WP-Cache doesn’t seem to have any mechanism for supporting such a response, and since it essentially “takes over” when serving a cached copy, WordPress never gets a chance to respond. I’m not 100% sure I did this right, but I managed to hack up the WP-Cache plugin so it looks for the “If-Modified-Since:” header and, if it the specified date is not earlier than the cached copy, returns a 304 response. Seems pretty straightforward, but I’m nervous enough about it that I’ll postpone sharing the code until it’s had a chance to simmer.

These changes should have a positive effect on both my bandwidth (for whatever it’s worth) and CPU usage. But more importantly to you, they mean faster page loads in your browser, and faster subscription refreshes in your aggregator. And hopefully I’ll fall out of first place in your NetNewsWire bandwidth abusers list!

Update: My changes to WP-Cache seem pretty stable in that they’ve been running on my blog for a week or so. If anybody is interested you can download the modified file here. The only change is to the phase1 script. The mods add support for 304 responses even on cached items, and for printing the elapsed time of page load even when cached.

Let me know if you have any feedback!

Update: If you are using PHP5, you will want to make a minor tweak to WP-Cache to fix a “blank pages” bug. See this page for more information.

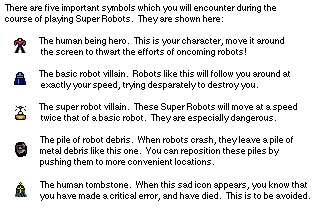

I got sent down a path of nostalgic code review today. After spotting Wouldja Software’s RoboNuts, I couldn’t help but wonder if the source to my implementation of the same game from more than 10 years ago was still on my computer. I was beginning to think it was lost forever to some floppy disk backup at the bottom of some storage closet, but sure enough Spotlight found it!

I got sent down a path of nostalgic code review today. After spotting Wouldja Software’s RoboNuts, I couldn’t help but wonder if the source to my implementation of the same game from more than 10 years ago was still on my computer. I was beginning to think it was lost forever to some floppy disk backup at the bottom of some storage closet, but sure enough Spotlight found it!