Shark Bites Script

October 17th, 2005Most Mac developers have, by now, given Apple’s CHUD Performance Tools Suite at least a cursory run-through. These tools, and in particular Shark, are incredibly effective for pinpointing performance problems that may be plaguing your application (or other code).

The presence of these tools has helped many developers inside and outside of Apple produc more efficient code. By effectively painting the low hanging fruit neon green, Shark allows us to easily locate our most embarrassingly slow code – hopefully before anybody else does.

One area of “coding” on the Mac where optimization has been sorely overlooked is that of AppleScript authoring. AppleScript performance can range from instantaneous to mind-bogglingly slow, and usually clocks in at some random level between the two, having been left complete up to chance by the script’s author. While laziness in the past may have been excusable, poor script performance is inexcusable in a post-Shark world.

Chumming Along

When professionals want to lure a shark nearby for viewing or killing pleasure, they may litter the water with visceral mix of blood and flesh: irresistible to the carnivorous beasts. Luckily, attracting Shark to your AppleScript is much easier to stomach, if you know a few tricks.

In AppleScript, as in other code that is executed in linear fashion by a computer, it is frequently most interesting to examine the performance metrics over a quite specific period of time. If you’re experienced with Shark, you may know that a clumsy method of starting and stopping the sampler is provided by way of a keyboard shortcut. This is useful, but often not precise enough for gauging the minute differences between scripting choices. By taking advantage of the the often-overlooked chudRemoteCtrl tool, which can be used to (among other things) remotely start and stop sampling in the main Shark application, we can get fairly precise performance details which are furthermore broken down by process, a detail which can be especially useful in assigning blame.

Preparing Shark for Duty

We can put control of Shark literally at our fingertips, but as the CHUD tools do have some eccentric behaviors, there are a few steps which must be followed to prepare Shark for reliable, scripted obedience:

- Launch Shark

- Ensure that Shark is set up for “Remote” control. This is off by default but can be turned on by selecting the “Programmatic (Remote)” menu item from the Sampling menu.

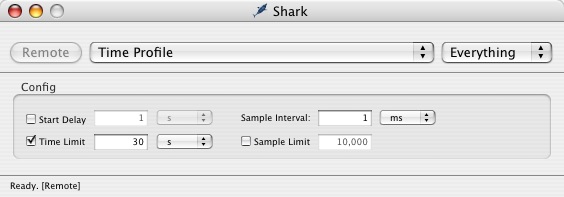

- Ensure that all sampling settings are to your liking. You probably want to target “Everything” as opposed to a specific process, because a given AppleScript is liable to enlist the help of many processes to achieve its goals. If your Shark window looks more or less like this, then you’re probably in good shape:

- Optional: Since sifting through the large quantity of data Shark produces can be daunting, it may be helpful to quit as many running Applications as you can before running your tests.

The power of Shark is now “cocked and ready to fire.” Next we’ll look at what we need to do from an AppleScript to take advantage of this potential.

Unleashing the Beast

Programmers familiar with using Shark from languages like Objective-C or C++ may be familiar with the CHUD library calls that allow procedural starting and stopping of Shark’s profiler. While AppleScript doesn’t include this functonality, we can take advantage of AppleScript’s shell scripting interface to invoke a powerful tool: chudRemoteCtrl. By passing the appropriate arguments to this tool, we can easily start and stop the profiler during the execution of a script, while giving meaningful descriptions to the associated sample sets that are generated as a consequence.

To demonstrate the power of this technique, I will use Shark to profile the performance of an extremely trivial example script. This scripts purpose is to compute the 64th power of 2, through methods ranging from completely idiotic to downright obvious. I chose this example simply to give you dramatically different performance numbers to compare. In real life, the numbers may not always be as “no-brainer,” but the same principles apply.

on run

-- Run some tests

set powersOfTwo to 64

my SharkStartSampling("Shell Scripted Dumb Calculator")

set worstResult to 2

repeat (powersOfTwo - 1) times

set badScript to "echo '" & worstResult &"* 2' | bc"

set worstResult to do shell script badScript

end repeat

my SharkStopSampling()

my SharkStartSampling("AppleScript Built-In Dumb Calculator")

set betterResult to 2

repeat (powersOfTwo - 1) times

set betterResult to betterResult * 2

end repeat

my SharkStopSampling()

my SharkStartSampling("AppleScript built-in expression")

set bestResult to 2 ^ powersOfTwo

my SharkStopSampling()

my SharkStartSampling("Null Operation")

my SharkStopSampling()

end run

on SharkStartSampling(sampleLabel)

do shell script "chudRemoteCtrl -s " & quoted form of sampleLabel

end SharkStartSampling

on SharkStopSampling()

do shell script "chudRemoteCtrl -e"

end SharkStopSampling

Paste the above code into your script editor and, after double-checking that Shark is “ready”, run the script. It’s important to keep Shark happy because it seems to misbehave after unexpected events like attempting to start sampling twice without ending the previous sample. If you get into trouble, you have to quit and relaunch Shark, putting it back into the prepared state described above.

As the script runs, you’ll see Shark processing samples and popping up analysis windows – one for each of the named tests I included in the script. When the script is complete, take a look at the resulting data sets. The first thing that strikes me as I look at the results on my PowerMac G5, is that the dumbest of all the code takes at least 10 times longer to execute than the smartest. As you look at the results in Shark, you can focus on particular processes and apply the powerful data mining utilities to eliminate uninteresting stack calls. For instance, in a real world situation, you will often only be interested in the samples obtained from the program your script was executed in, and the program your script is “telling” to do something (if applicable).

As you glance through the resulting sample sets, you may notice that even the smartest technique comes up with a significant number of samples. There is some overhead to the profiling mechanism, and being a multi-tasking system, the other processes on your computer may be stealing time away from your test. For this reason, I included as a final example a “null operation” which simply starts and stops sampling as quickly as possible. On my computer, the total difference between the control case and the “built-in expression” case is only 15.7ms. By comparison, the dumbest case clocks in at a whopping 8 seconds!

In Summary…

Clearly this example was an extreme case of low hanging fruit, but the principles can be applied in any script to obtain information about its effect on any process in the system. You may also find yourself using this technique to verify or dismiss suspicions about the software you use. What exactly happens when an application asks the system to beep? Is perl faster than ruby? Does iTunes hesitate just a bit longer than usual when asked to play a Britney Spears song? Only one way to find out…

An Update…

On the AppleScript-Users mailing list, Has makes some interesting points about this approach. He points out that, because Shark doesn’t gather data about the particular AppleScript subroutines that time is spent in, it can’t really be described as profiling the script. While I think this is a fair point, I maintain that it can be very useful to figure out where the system is spending time while executing your script. The nice thing about Shark is that it will represent samples from code in any process that was invoked to fulfill the demands of your script. True, if your script is 100% AppleScript and doesn’t invoke any scripting additions that reach the system APIs, then the profile might be kind of boring, but that is in itself informative as well.